The One Hand & Six Fingers

Writers: Ram V, Dan Watters

Artists: Laurence Campbell, Sumit Kumar

Colorist: Lee Loughridge

Letterer: Aditya Bidikar

Publisher: Image Comics

Collects: The One Hand, #1-5, The Six Fingers #1-5

Publication Date: December 2024

In the second issue of The One HandDetective Nasser enters an art exhibit in the hopes of finding a lead on a serial killer, and overhears a conversation between two other guests: “…cannot be about finding meaning… it’s about creating Item. To assume meaning exists to be ‘found’ is a betrayal of the endeavor… Everything is not art. Everything “can be art.”

This off hand remark by some art enthusiasts debating a classic aesthetic question encapsulates the entire thematic interests of both The One Hand and The Six Fingers. Both books take the idea of what can be art and turn it into their central existential question: is meaning intentional, grounded in experiences that form patterns we can become privy to? Or is meaning absurd, the simple act of giving intentionality to events that are random and themselves meaningless? On the one hand, we have a Sartrean detective, a man who’s entire job depends on seeing the patterns, meaning given to him by the world and stitching it into narratives about justice. On the other hand, we have the Camusian archaeologist, the discoverer of objects from the past that have become emptied of all meaning, a man driven to give life to things that are otherwise meaningless.

The One Hand and The Six Fingers are two separate five issue mini series that discuss similar events from different perspectives. The first, by Ram V and Laurence Campbell, follows Detective Ari Nasser on the eve of his retirement. Right before he calls it removes, he’s drawn into capturing a serial killer he’s thought to have caught two other times, the One Hand Killer. The complimentary series by Dan Watters and Sumit Kumar, follows Johannes Vale, an archeology student who slowly loses control of his life and follows the path to becoming the One Hand Killer. The two books alternate chapters and meet specific inflection points but never collapse entirely into each other. At no point are Ram V and Dan Watters simply trading off writing duties. The One Hand and The Six Fingers are two different stories, with two very different protagonists whose experiences and arcs are represented differently by the artists on each book. Their connection is more along the lines of mirror reflections, and never reducible to a typical comic book crossover where the end of one issue is the beginning of the next.

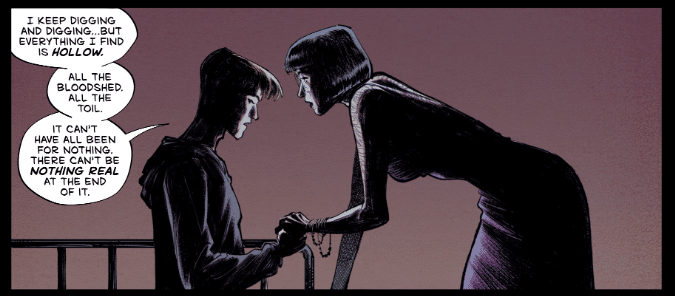

Nasser and Vale are both on a quest for patterns, trying to find frameworks that allow them to reduce the chaotic and nebulous whims of the universe down to digestible forms of recognition. Violence and murder aside, this is something we all do. We must turn the randomness of life into forms of meaning, into patterns that are easy to understand simply as a survival mechanism. Our thoughts are invariably about or of something, reaching out into the world towards some end, whether it’s there or not. The trouble, however, is to confuse that primal psychological need and its functionality with some larger divine order. We form knowledge to navigate the world, but nothing is able to sufficiently confirm that the world is knowable in itself.

In one of their confrontations, Vale lays out for Nassar that the truth is for him to find, but not for Nassar to know. Rather than a traditional cat-and-mouse game of cop and killer, these two don’t form opposite poles of a moral dichotomy, but rather they are on parallel tragedies of an epistemological nature. Vale’s quest for truth is not to be confused or conflated with Nassar’s desire to know for his own comfort.

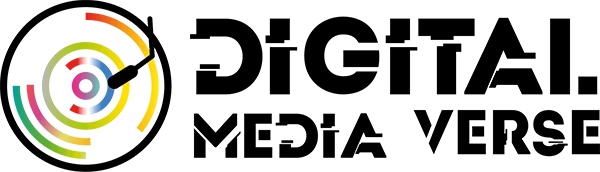

For Nassar, the quest to uncover some truth, to form some pattern, is the action animating his entire life. Nassar thus can never have access to reality, to some objective truth, because his knowledge is ultimately about function. The truth is what makes sense within the confines of how he thinks the world works: how he can build his case against criminals, and how it can be used to bring order to the hellish future of Neo Novena. This principle is so dominant that even the panels of the story start to mirror the ciphers of the One Hand Killer, an admission that this mystery defines Nassar’s whole experience of the world.

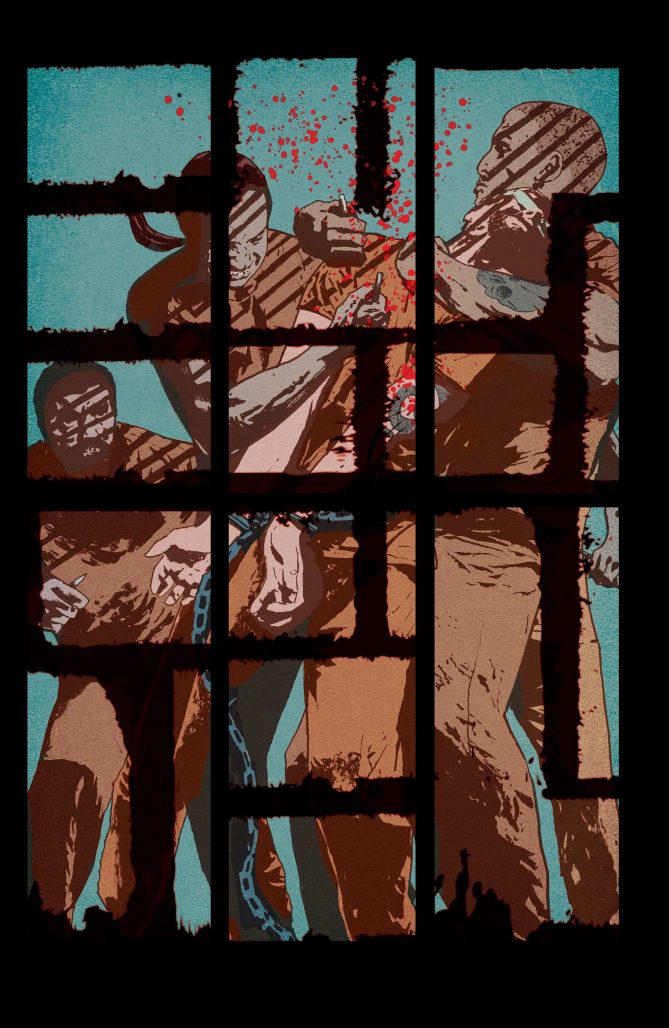

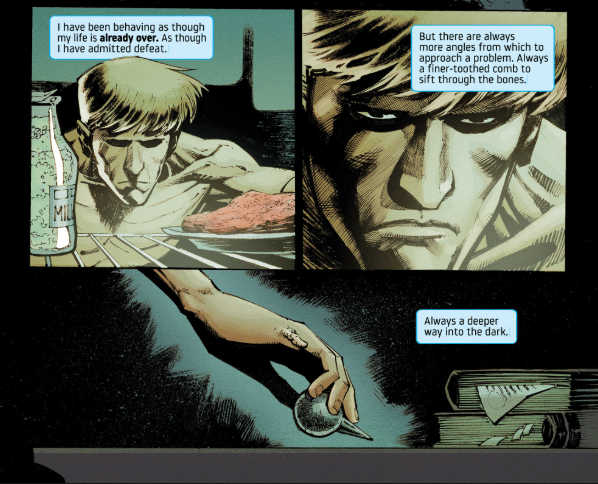

Nassar’s story is something akin to blade runner with our neo-noir detective coming to terrifying existential realizations about himself and the world. Thus, Laurence Campbell and Lee Loughridge’s art is appropriately moody, with extensive use of shadows, silhouette and neon lights clashing with the darkness.

Like a traditional noir, the truth is found in the dark because the day is often illusory, the product of whatever lies and dirty dealings occur at night. Thus, each step in Nassar’s realization of the world has him moving more and more into the dark, more and more into the shady corners of the world until he steps out of reality altogether. In the final pages of Nassar’s story, order collapses not just in the form of the world he believed in but in the pages of the comic itself, as the panels break down and the skeletal text takes over. Nassar in these moments realizes that we do not uncover truth, for if we did we might end up rejecting reality altogether. Rather, we stitch together perception, events and ideas into a shape that gives meaning to chaos, for that’s the only way to live in this world at all.

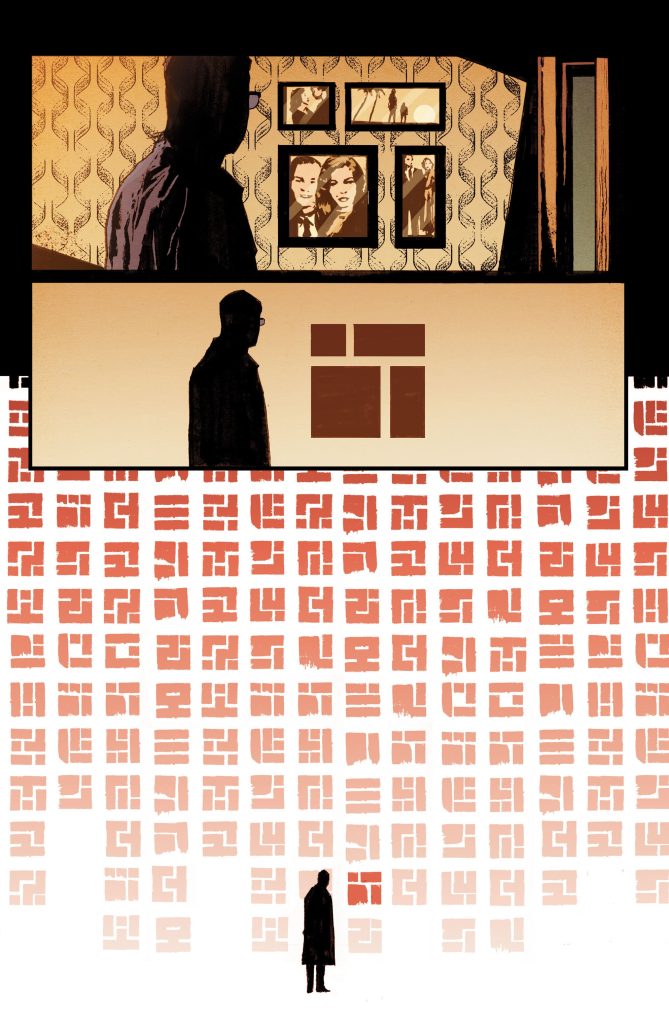

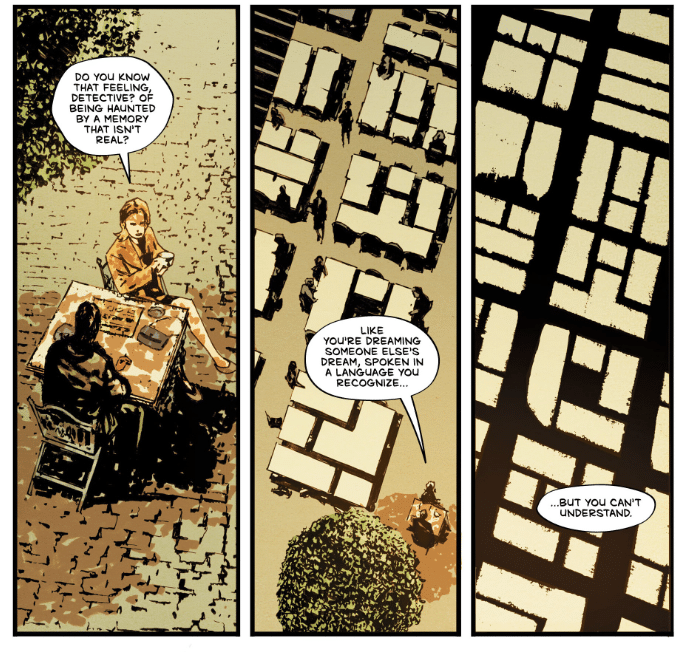

On the other hand, Vale’s story is more like The Matrix. Also colored by Lee Loughridge but this time with art by Sumit Kumar, the pages of The Six Fingers are more open to the reader. The sun exists, colors are mutated but present. We’re allowed to see the world in front of us with some degree of clarity before Vale’s descent into darkness. Despite these more lively exterior elements, Vale is unable to accept the simple answers he’s given about himself or his past. The universe appears to have given him everything a person would want: a job, a graduate research program and a girlfriend. But Vale is not content with these approximations of satisfaction, he craves to find the truth in the gaps. He is after all studying archeology and in that process he ends up digging far too deep.

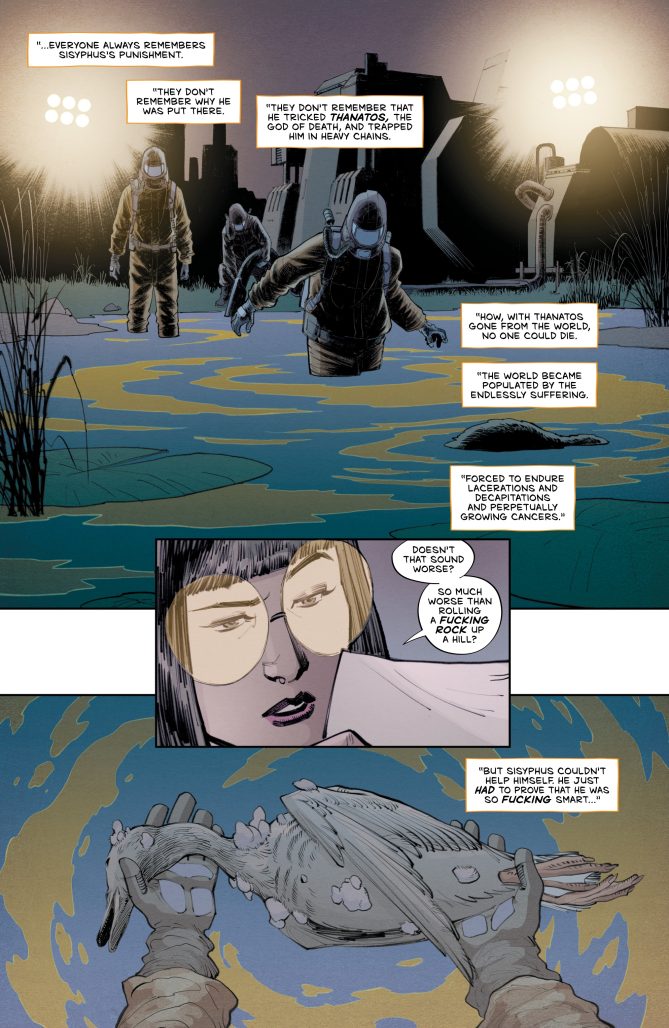

Watters directly references Vale’s connection to the Myth of Sisyphus, which makes sense particularly in relation to the earlier ideas of meaning and patterns in the series that parallel concepts within Albert Camus’ philosophy. Vale seeks to escape the punishment of this cyclical world but Sisyphus/Vale’s quest to outsmart the “natural” order can only ever end in tragedy, for how can anyone disrupt the accepted ontology of the world without casting themselves out in the process?

“Archaeology” is an interesting choice here, as the term in relation to questions about reality and truth parallel the early work of Michel Foucualt. This archeology deals with knowledge and discourse, the systems of meaning and exclusion that ideas are folded into. Akin to Foucault, Vale finds meaning in writing, both in his journal read throughout the series and in the form of ciphers left by the One Hand Killer. The ciphers are not just messages, but structures that organize the events of the comic, designed in a way to mimic the panel layouts or at times replace those traditional layouts altogether. The structure of the ciphers is everywhere in the comic, and this need to escape the literal confines of truth discourse becomes Vale’s primary goal.

In his inaugural lecture at the Collège de France, collected in The Archeology of KnowledgeFoucault notes “it is always possible one could speak the truth in a void; one would only be in the true, however, if one obeyed the rules of some discursive ‘policy’” Meaning that objective truth may or may not exist, it may be possible to study or quantify it in some sense. But being “in the true,” as in being part of society and giving the truth purchase as an organizing principle of people, is only possible if it’s useful, if truth makes its way into function and our modes of discourse. Vale’s journey is to break out of systems of discourse, to find the very truth in the void that would be incompatible with the order of the world. Whether that’s possible or desirable remains an open question.

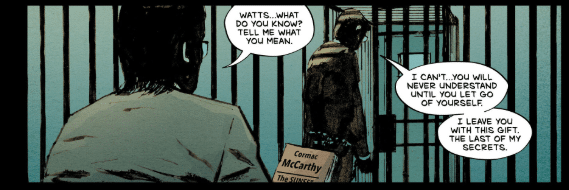

The series is also inspired by Cormac McCarthy and his play, The Sunset Limited. The characteristically unconventional play follows only two characters, White and Black, who discuss the meaning of existence, life, and God. While the play was adapted into a film later, it reads more like a novel, and shares its style with McCarthy’s final work, Stella Maris. In both cases, McCarthy is less interested in rehashing the history of philosophical debates and more interested in the material realities of grief, finding purpose, and how our identities are constituted through each other in discourse. Both texts are ripe with contradictions, demonstrating to the reader that arguments aren’t won by the validity of their structure or their correspondence to reality, but by the conviction with which they’re argued, by the desire to fight tooth and nail for slivers of meaning that says more about us than about the uninterested universe around us.

Thus in the world of The One Hand and The Six Fingersreality is a choice we have to make. Either we argue for our purpose, for what defines us and what makes us feel like we have some sense of control. Or we give in to the lack of meaning, denying reality and ourselves, succumbing to our own nothingness. Or as McCarthy wrote in All the Pretty Horses: “If there is a pattern there it will not shape itself into anything these eyes can recognize. Because the question for me was always whether that shape we see in our lives was there from the beginning or whether these random events are only called a pattern after the fact. Because otherwise we are nothing.”

When looking at the two books together, there is also an element of how they deny us the satisfaction of being neat call-and-response pieces. The One Hand is as much its own story as The Six Fingers is, and the desire to try and stitch them together to see if one issue holds a more clear answer to the questions posed in another issue is largely futile. Maybe you can figure it all out, maybe you can’t. But the comics call us to do the very thing they say is so absurd in the first place: trying to find patterns, presuming that meaning is anything but personal intentionality injected into the randomness before us.

Indeed this embodiment of their themes also goes a long way in squaring the existential questions with the aesthetic ones that we started with. What does it mean to say “Everything can be art?” Ultimately, it’s all a matter of perspective. Art, like Vale and Nassar, or like The One Hand and The Six Fingersis co-constitutive. The audience and the art, or the art and the artist depending on what side you’re on, create the meaning behind the art together. How we look, what questions we choose to ask, and how the works motivate us to ask specific questions is how we come to understand what art is. This aesthetic character, the practice of how we come to experience art, is then a training ground for how we wrestle with larger existential, moral, and epistemological questions all around us. If art is co-constitutive, why not meaning? Why not reality? Why not the whole world? And if that’s the case, who or what has the power to create while others only observe? And what responsibility do we have in creating when there are others who will inevitably see our work?

The One Hand and The Six Fingers are tremendous existential musings, reflecting two different searches for meaning that inevitably come into conflict. While their inspirations, both in philosophy and in other media, are clear throughout, their execution is excellent and will likely keep you up at night asking the all too real questions: do I exist? and What’s the point of all of this?

The One Hand & Six Fingers is available now

Read more great reviews from The Beat!