Junji Ito‘s most popular works tend to focus on the kind of darkness that lives in fixation and obsession. in Uzumaki it’s represented through spirals and how people twist and contort themselves to become them. in Tomie It takes the form of the titular girl, a mysterious figure that men fall head over heels for only to find body horror at the tail end of attraction. in Gyoa man gives himself entirely to take care of his partner beyond the point of no return after dead fish on mechanical legs start terrifying people. In these stories, obsession leads to either self-destruction or societal collapse. What’s less commented about these stories is how aggressively satirical they are.

When you’re getting scared by a master storyteller, it can be hard to look at the things operating behind the scenes. I know I was too busy being scared to get it the first time I read these books. Ito’s 2005 sci-fi horror tale Reminathough, is perhaps the most obviously satirical one in the creator’s oeuvremaking it quite easy to see what the intention behind the hellish imagery was. And it is truly hellish imagery.

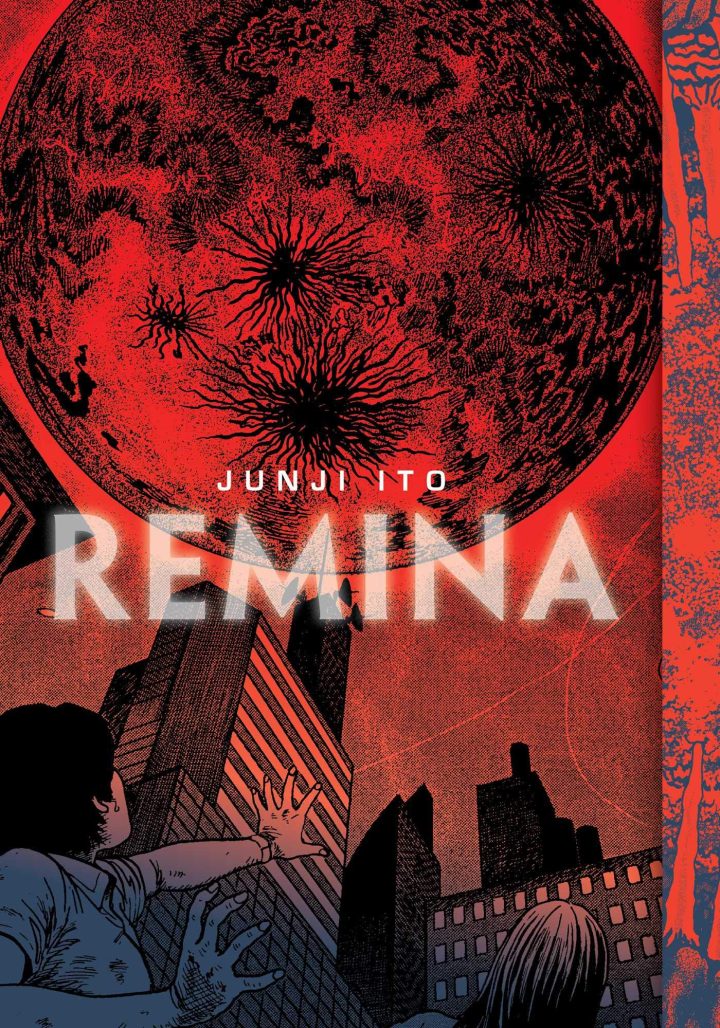

Remina centers on a demon planet that’s heading towards Earth, swallowing up stars and planets along the way. A Japanese scientist discovers the planet, naming it Remina after her daughter. Human Remina becomes a star overnight, sparking the rise of fan clubs and talent agencies that chase after her. As the demonic celestial body closes in on Earth, humanity realizes that this thing is driven by an insidious hunger that won’t just decide to fly over us. Here’s where the satirical element starts creeping in. The public arbitrarily reaches the conclusion that the planet is being controlled by the scientist’s daughter because they share the same name. From there, fame shows just how bad it can turn on those under its light.

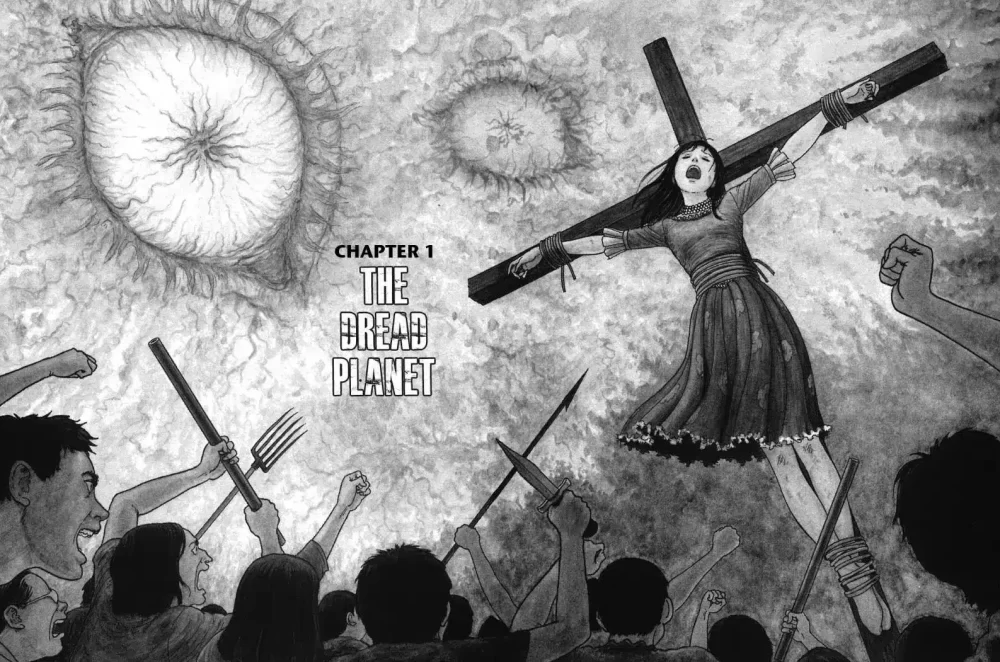

Things go off the rails pretty fast, worryingly so for the characters. Ito use the name association argument the populace settles on to explain planet Remina’s apocalyptic hunger to point at how ridiculous the roots of fear can often be. Mob rule becomes the standard almost immediately, and the first order of the day is raising crosses to crucify the scientist and the daughter to see if that appeases the demon planet. It’s as if the crosses were made in advance and stored nearby in case of a global crisis, brought out just as the need presented itself.

It’s all absurd and darkly comic but also terrifying as it points to how fast people can rally behind the bones of an explanation, going from fear to mob violence in the blink of an eye. And yet, Ito builds his satire on human Remina’s swift rise to pop icon status, which frames the mob as a rabid mass of fans that are obsessed with not only possessing the object of their desires but also finding in it the cause for all their problems .

It’s a smart approach that really points the finger at fandom as a big problem with real life horror potential. Things grow from that core idea, tethering themselves to that fandom problem in multiple ways. Planet Remina, for instance, possesses a giant eye that opens just as it reaches Earth to get a better look at the ridiculousness taking place below it and how it’ll fail to stop the inevitable. In a sense, it becomes a spectator, a Big Brother presence that’s momentarily joined in on the fandom before it finally gets tired of it and eats it. Remina doesn’t judge humanity. It is fascinated by its absurdity (a sentiment those on the opposite side of fandom are well acquainted with).

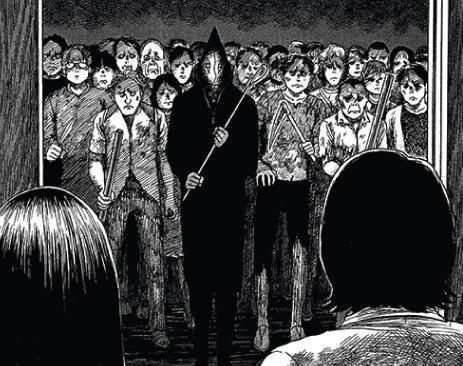

The idea extends to human Remina’s pathetic band of protectors, among them her agency representative, the president of her fan club, and a guy who wants to marry her. And this is all just the tip of the iceberg. Ito finds even more ways to complicate and expand on the concept, most notably with a homeless man who isn’t as up to date on who’s who in this scenario because of his life circumstances. We also see a group of hooded figures that claim to have Earth’s best interests at heart by driving the point about the crucifixions even harder. It gets more absurd as it progresses (to a degree that only the book Gyo might come close to).

Remina is Ito at his most satirical. There’s a frustration with fan culture and mob thought that’s palpable here. The demon planet at the center of the story is a reflection of the people who lose themselves in that environment, a sick and always hungry being that decides to interrupt their feeding to fixate on the human drama. In the end, Remina is us, and we are Remina. We will stop what we’re doing to indulge our obsessions, and only after we’ve grown tired of them do we turn our backs and cast them into oblivion.